Seth Crane, a young man from Tasmania’s North West Coast, recently took his own life at just 19 years of age. His uncle, Star Weekly journalist Cade Lucas, reflects on the loss of his nephew and the numbing experience of youth suicide.

It’s one of those moments that makes you wish smartphones didn’t exist. If I had a flip phone, a Nokia or one of those bricks from the 1980’s that needed to be tuned in like a radio, I likely wouldn’t have known, at least not straight away.

Better still, if there were no mobiles or internet, my week off down the Surf Coast would’ve continued in ignorant bliss until I got back to Melbourne at the weekend and my landline rung with someone bearing bad news.

Instead, I was standing on a lookout above Bells Beach, only a few hours after leaving home, using my smartphone to take pics of the surf below when it buzzed with one of its many other functions.

It was my older sister Erin messaging the family group chat.

Erin’s calm, sensible and taciturn so the fact her message began with a profanity repeated three times in a row hinted that the rest of it wasn’t good.

And if the previous 19 years were any guide, something to do with my older sister that wasn’t good likely involved her eldest son.

Seth had always been a difficult kid.

He was loud, rude and could be stunningly self-centred. He was prone to wild outbursts that would upset those around him, but for which he showed little or no remorse.

His ears were deaf to the word ‘no,’ he had no concept of the word ‘share’ and ’sorry’ was just something to say to get out of trouble rather than a word with any real meaning.

The rest of our family used to (only half) joke that Seth would end up in jail by the time he reached adulthood, yet when he did get there, his vast reserves of energy had been channelled towards something much more positive.

His thirst for attention, absence of shame and ability to charm and manipulate at will saw him gravitate towards performing arts rather than prison, and having finished high school in Tasmania last year, he recently started work as a theatre assistant at a local private school.

That he’d only sporadically attended school himself and needed ChapGPT to disguise the fact he was functionally illiterate, made it even all the more impressive.

He still had rough edges; empathy and generosity weren’t strong suits and neither was financial management or personal hygiene, but these were neither here nor there.

They didn’t matter.

Seth was on his way and he was gonna be fine.

He had an abiding passion that he was pursuing and he had the combination of charisma and chutzpah to bluff and bullshit around any obstacles that lay ahead.

It’s why I wasn’t too worried when my mum told me last year that Seth has spent time in a in the mental health unit at Burnie Hospital after breaking up with his long-term girlfriend.

And it’s why I was concerned, but not too concerned, when I learnt that Seth had recently gone back there after the end of another relationship and that having been discharged, he’d been re-admitted again.

And it was why, after reading the rest of my sister’s message and learning that earlier in the afternoon, nurses at the unit had found Seth unconscious following a suicide attempt and that after performing CPR and keeping him alive, he was now in ICU, I felt more stunned and numb than outright concerned.

After replying to her message with some profanities of my own, I stood there on a sunny spring afternoon above the waves crashing below, feeling more worried about the welfare of my older sister and for my parents who were on holiday in Spain, than I was for my nephew who was now breathing with help of a ventilator in a hospital on the other side of Bass Strait.

Afterall, he was alive and in the best of care. And he was Seth. He always found a way. He’d be alright. Wouldn’t he?

I avoided answering that rhetorical question as I left the lookout, destination unknown.

I’d only left that morning on a whim and in typical fashion hadn’t organised anything, but I’d come too far to turn around now and what was there to turn around for?

I was on holidays and had come down here to get out of the house, so I wasn’t going back. And I couldn’t organise trip down to Tassie and wouldn’t be of any use down there even if I could.

And I wasn’t certain that was even necessary because, after all, Seth was gonna be fine, right?

My mind was scrambled to the point where I probably shouldn’t have been driving, but drive I did: Anglesea, Aireys Inlet, Moggs Creek and finally to Lorne where I booked into an overpriced room in a cheap motel, just in time for my sister to send a picture of Seth hooked to a machine in the ICU.

His hair was dark, thick and shaggy like mine at the same age. His eyes were closed. He looked at peace.

The sun was up in Spain and my parents said they were cutting short their tour and looking at ways to get an early flight home. I’d contacted my brother who’d long checked out of the group chat and after a flurry of sorries and swear words, everything went calm.

I spent a couple of days wandering around Lorne trying to pretend things were normal, before heading off to Apollo Bay feeling slightly optimistic.

Seth was now breathing on his own and was booked in for an MRI on Friday afternoon.

I lulled myself into thinking the worst had passed when Erin dropped another message.

It was Friday night and I was having a drink at the pub when I opened and read it.

There were no swear words this time, just a matter-fact update on the results of the MRI which showed Seth had suffered too much brain damage to ever regain consciousness.

By the time I got to the crying emoji she’d posted at the end I’d already made it redundant.

The next day I drove home via the inland route to avoid any reminders and on Monday I returned to work; the deadlines that I’d recently sought to escape now provided a timely distraction.

But while Seth was no longer alive, his healthy heart and lungs meant he wasn’t dead either. So for the the next two weeks I found myself in the purgatory of wanting to to tell people about it, but not wanting to add a qualifier like “he attempted suicide and was mostly successful.”

The lag period allowed my parents to complete their trip and come home (they decided against spending $10,000 on new flights to return three days early) and also for my youngest sister Peri, to return from overseas too. They took it in turns staying with Erin at the hospital while Seth slowly passed. Mum spoke to him. Peri painted his toenails.

By Melbourne Cup Day, a fortnight after attempting suicide in another part of the hospital, he finally succeed.

As was now customary, Erin delivered the news with a simple message to the group chat. It was a relief.

Since Apollo Bay, I’d been thinking about Seth in the past tense anyway.

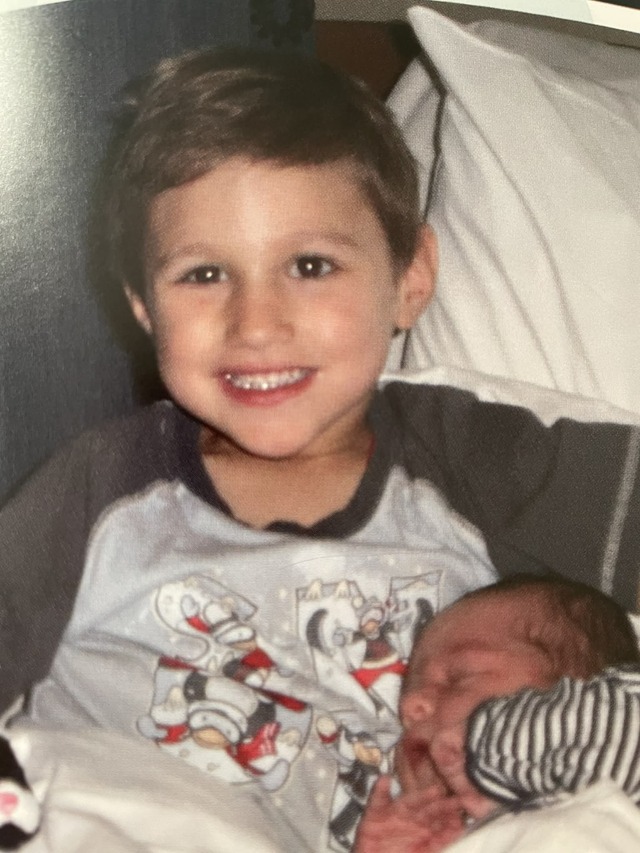

I’d been thinking about the first time I met him as a baby at my sister’s old place in Burnie, near the hospital where he died. About the force of nature he was as a little boy, a wrecking ball trapped in an infant’s body. About how since moving to Melbourne in 2009, I hadn’t seen much of him, yet I still witnessed him grow-up. His mother posting pictures on Facebook messenger helped. So too his outsized personality that transcended any distance.

I remembered trying to be a good uncle and messaging him during his relationship struggles, telling him that I was there if he ever wanted to talk. I got a cheery ’Thanks!’ in reply.

I recalled that in more recent years as he grew taller, we’d stand back to back to see who was now tallest in the family. Having conceded the title a few years ago, I wasn’t planning on regaining it so soon.

I included some these anecdotes when I spoke at Seth’s funeral last month. It was much bigger and also much worse than I expected. Seth’s fabulous flamboyance won him a lot of friends. All of them were distraught.

Everyone knows suicide is bad, youth suicide especially.

Yet the reality is immeasurably worse than I could ever have imagined.

I don’t think I’ll be going back to the Surf Coast.

Lifeline: 13 11 14