Health promotion organisation Women’s Health in the North is working to address economic equality for women. Cade Lucas reports.

When Manasi Wagh told me her official title, I had to ask for clarification, thinking I may have misheard or made a mistake.

“I’m manager of economic equality at Women’s Health in the North,” she repeated confidently, as though there was nothing unusual about economic equality being a focus of a women’s health organisation.

That’s because as far as Ms Wagh, Women’s Health in the North (WHIN) and other like-minded organisations are concerned, there isn’t.

“They’re interconnected,” she explained of the relationship between economics and health before adding the obvious rejoinder: “money and finances underpin everything in our lives.”

As far as statements go, they don’t get much harder to argue with than that, though just in case I wanted to, Ms Wagh wasn’t done.

“People experiencing financial distress are twice as likely to experience mental distress at the same time,” she told me, before reeling off a stream of statistics showing women were far more likely to experience financial distress than men.

“Currently the gender pay gap is 21.7 per cent which means that every dollar a man earns, a woman earns 78 cents,” Ms Wagh said, adding that the gap in superannuation upon retirement balloons to 47 per cent, with women leaving the workforce to have babies and being more likely to work part-time, the biggest factors.

That’s assuming women reach retirement age with a job at all.

“In Australia the statistics for women over 50 are pretty grim,” she said.

“Forty per cent of women over that live in poverty or will retire in poverty, with rates of homelessness high as well.”

For all of these factors, migrant women and those from non-English speaking backgrounds are worse off again, with cultural factors often adding another degree of difficulty on top.

“Our work is focussed on reducing these inequities,” said Ms Wagh of WHIN, one of 12 such health promotion agencies set up across Victoria.

While originally established to serve the large migrant communities of Melbourne’s northern suburbs, Ms Wagh explained that as with the word health, the title should be taken too literally.

“Even though the organisation is situated in the north, the economic equality work we do goes across Victoria.”

As migrant herself, who moved to Australia from India in 2006, Ms Wagh knows intimately how important that work is, particularly in regards to money and finance.

“I came here as an educated person, but still struggled to know which bank to go to and what accounts to open because the names were different, the terminologies were different,” she recalled.

“I did not know what my financial rights were, what my responsibilities were, so these things are all taken into account in designing the program.”

That program is Lets Talk Money, which WHIN have been offering since 2017.

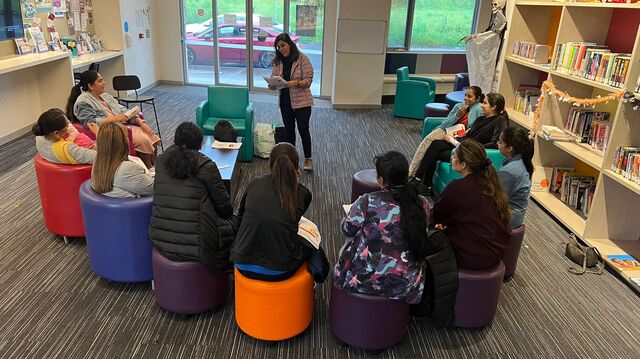

Lets Talk Money (LTM) provides tailored financial education to multicultural women through a peer education model where migrant women are recruited and trained in financial literacy, to then educate others from similar backgrounds.

“This approach has proved very successful because not only do the educators have the language skills and cultural understanding but the lived experience of migrating to this country,” said Ms Wagh.

One of them is Maria Zygourakis, the daughter of Greek migrants, who while born in Australia, grew up witnessing her parents struggling to understand the financial realities of their adopted home.

“Many, many times they’ve talked about the language barriers, or the cultural barriers they faced, yeah, when they first arrived,” said Ms Zygourakis who has been teaching financial capability classes for more than two years.

She said given the broad nature of the topic and the even broader range of clients, a needs analysis was conducted before each session to identify the issues to be focussed on.

“For example, recently, I had a group that were elderly Greek migrants, so they wanted somebody to come from Centrelink to talk to them about pensions and assets and property,” she said.

“And then there’s other groups that have recently arrived, and might want to know the simple information such as, how do you open a bank account in Australia and what identification is needed? What are the different types of cards?”

Translating documents, explaining economic jargon and ensuring bills or fines are paid on time are other simple tasks participants are helped with, but which can cause serious problems if not understood.

Ms Wagh said cultural issues around women and money and the social stigma associated with financial difficulties are also addressed.

“There’s a shame attached to it ‘oh I cannot manage my money,” she said.

“If you put that together with family violence and financial control, it’s a deadly cocktail.”

As in all other sections of society, family and domestic violence is a huge problem in multicultural communities.

But according to national prevention of violence against women not-for-profit, Our Watch, the financial dependence many migrant women have on violent partners, makes them especially vulnerable.

“Asylum seeker women living in the community on temporary visas, as well as migrant women on student and working visas, are not entitled to social security payments. Migrant women also experience other kinds of financial insecurity, including discrimination and racism in the labour market.”

Social isolation due to a lack of family support, language barriers and even being more likely to live in outer suburbs or regionally, where access to transport is difficult, are other barriers to migrant women escaping violent relationships.

For Ms Wagh, it’s this issue where the overlap between women’s financial and physical health is most important.

I worked in the health sector and have worked in the family violence sector and the prevention of gender based violence and economic equality kind of sits alongside it,” she said. All this work WHIM, LTM) is to prevent gender based financial abuse. It’s my passion in life.”