They have the wisdom of lived experience, knowledge passed into their care, and a responsibility to ensure younger generations never forgot where their story began. Benjamin Millar meets the elders keeping their heritage alive against the onslaught of rapid societal change.

NEAR a bend of the Maribyrnong River sits a remnant cluster of eucalypts. As the river slips silently by, Uncle Roy Alexander will often be found among the trees; listening, reflecting. He readily admits these eucalypts have been his saviour. Without them he may not be here today.

“For 30-odd years I’ve had this family. Before that it was, ‘I just want to get out of this world, I can’t take the pain, I can’t take the nightmares, can’t take any more’.”

Uncle Roy recently discovered he is part of the Stolen Generation, a moment the jigsaw pieces finally began falling into place.

“They took my soul. My mum died going insane trying to find me. And there’s many of us. Many, many, many, many.”

Every Friday Uncle Roy can be found at Footscray’s Barkly Arts Centre, joining other Aboriginal elders in a ‘healing through art’ program run by Aunty Francine Riches.

She says the Western Region Health Centre initiative has been a remarkable success, culminating in a special Scattered Tribes exhibition held recently during NAIDOC Week.

“Art is healing. You get people to come and do art and once they are here, you find out what their other needs are in their own time.”

Before the art sessions the elders were fragmented. Aunty Francine says they had missed that sense of being part of group.

‘‘Even if they’re not doing a lot of art and they’re just talking, people open up and they begin to heal. They have a family here.”

It’s this sense of family that keeps Uncle Roy returning. He speaks with pride of the photographs he took of his ‘‘other family’’ for Scattered Tribes.

One image in particular stands out, a silver eucalyptus with a series of twisting and turning branches reaching for the sky.

Asked to nominate his favourite piece Uncle Roy doesn’t hesitate, walking straight to this image.

“That’s the one I’ve always called Mum. Someone with a carving knife has carved Macedonia right down the bottom here. I’ve tried to help her but she’s helped herself, she’s cleaned herself up,” he said. “I’m just taking pictures of my family like everyone else does.”

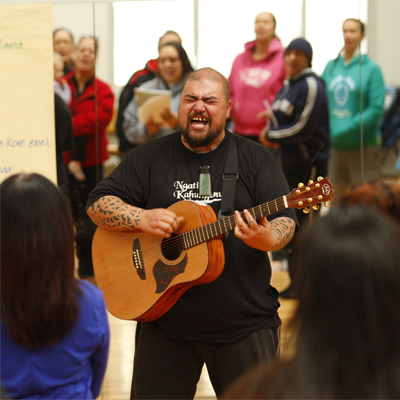

This broad notion of family resonates with Aunty Kiri Dewes. The Maori elder strives to teach younger Maori generations about their shared heritage.

Like Aunty Francine, she believes in the power of art and performance to draw people together. The energetic Melton grandmother keeps a dizzying schedule of community events and international engagements.

Aunty Kiri runs a self-esteem workshop in Williamstown for young women and can be found every Sunday at the Action Hall in Laverton, spurring young Maori Melburnians to pour their hearts into writing and performance.

“I work a lot with our youth. I write songs for them and they perform their dances. I teach them our language,” she said. “To me that’s our role as elders – to make sure our youth are on the right track and that they can live in both worlds, holding on to what belongs to them and moving forward in a western society.”

For Aunty Kiri, it’s about allowing young people to be themselves and to share what it is that’s on their mind.

“I say ‘I don’t know what’s going on in your head, but write it down and I’ll translate it’. I sit them down and say, stop using the thesaurus, write from the heart. It’s their vision, their dreams, their regrets. Then they bring it all to life in the performing arts.”

Sunshine Uniting Church pastor Penaia Te’o is experimenting with a different path.

Rather than the performing arts, he is working to engage and connect young Samoans on the sporting field. Te’o has helped start the Brimbank Rugby Union Club in the hope of keeping young people out of mischief.

He concedes the Islander community faces perception issues but believes most are doing the right thing.

“We have some who have problems changing from Samoa to their new country, the new environment.

“We do things differently in Samoa. Every place has a chiefs council and they are responsible for their own community. They protect the community from things happening.”

In Samoa it’s more acceptable for parents to discipline their children and for the broader community to have a role in pulling them into line.

“The whole community looks after them and says, ‘don’t do that’. The whole community protects itself.

“The chief may tell the family to bring maybe six pigs or one or two cows, or 100 taros. When the chiefs tell the young people, ‘sit down here and listen’ the young people will listen and the chief will talk to them and say, ‘don’t you ever do that again’, and the father of the family will tell them that it is a disgrace for the family. It is very effective.”

The church is important in bringing together the Samoan community and the reason Te’o first came to Australia in 1980. The church also holds a place in the Aboriginal community in Melbourne’s west.

Aunty Francine Riches says a lot has been done in the past in the name of God that has damaged Australia’s indigenous community.

Mission policies, policed by the government, caused a lot of harm. But there’s also a message that resonates with her people.

“We are a spiritual people, we understand about the spiritual world,” she said. “Many of the people that caused a lot of hurt in the missions weren’t representing the true message of the Bible. The true message of the Bible is love and forgiveness.”

The role of Aboriginal elders differs from area to area. But one experience common to today’s elders is the harm caused by displacement and decades of policies that have torn apart strong family ties.

Aunty Francine speaks of a great deal of hurt in Melbourne’s Aboriginal community and a need to deal with long and deeply felt suffering.

The success of the elders’ healing program has inspired her to look at how the same ideas can be used to help the community’s future generations.

“A lot more people are finding out about our art program and they’re really interested. We want to start up a young people’s group, there are a lot of young people who have found out about it and want to come and get involved.”

Te’o admits worrying about what the future holds for his community, including his 15 grandchildren.

“We’ve got to do everything we can to make sure they are protected. We are working towards the fulfilment of that goal of having a place for all our young people’s enjoyment, to be part of something. We would like all the community to come in and get involved. I believe this will be a good thing.”

Aunty Kiri has 20 grandchildren of her own, but is ‘nana’ to countless more.

Her eyes light up as she explains her determination to keep the Maori culture alive.

‘‘Our elders preserved our history in song, in our chants, so through the revival of chants, the Maoris have learned about land, where their fishing grounds are, what time to do certain things,” she said.

“For our young ones here it’s difficult for them to speak their own language, but they love the stories, the history, the genealogy. I know a woman who can only go back as far as her parents. I can go back to God’s children.”

As proud as she is of her heritage, Aunty Kiri is also open to what the rest of the world’s cultures have to offer.

She wants young people to “move comfortably in both worlds, to move with the times but don’t forget where your roots are. Remember you’re Maori, you’re from New Zealand, but learn to live closely with all the different cultures here.”

Next week Aunty Kiri will travel to Brisbane for the first meeting of her Council of 13 Grandmothers, elders from a range of different cultures who want to share their stories and wisdom.

Between her international speaking tours, poetry writing and involvement in keeping her young flock on the straight and narrow, one could be forgiven for thinking she may be ready to enjoy a quiet life after recently celebrating her 75th birthday.

But the suggestion receives short shrift.

“I reckon if I wasn’t doing what I’m doing now I’d be well and truly dead; long gone.”