NERVES wrack An ‘‘Andy’’ Nguyen’s body. Sweat trickles down his face as he leads his men through the jungles in Vietnam’s central highlands.

It’s early 1973 and Mr Nguyen, now a Footscray-based accountant, is at the head of his first patrol in command of an experienced but battle-weary platoon down to a quarter of its original strength.

As they move forward, probing for enemy positions, shots ring out from an enemy bunker in jungle and he calls his men forward.

Through the lenses of reading glasses, he mistakes the specs of bright light crowding his vision for sun glare and charges headlong towards the enemy position under a hail of machinegun fire.

The action, his first, last little more than 15 minutes. Most of the enemy forces flee, the rest are killed.

‘‘My men thought I was very brave and I didn’t care about the machine gun fire,’’ Mr Nguyen says with a laugh, ‘‘It wasn’t because I was brave it was because I didn’t know what was going on.

‘‘I was freezing, I was sweating and I thought ‘hey Andy, you nearly died’.’’

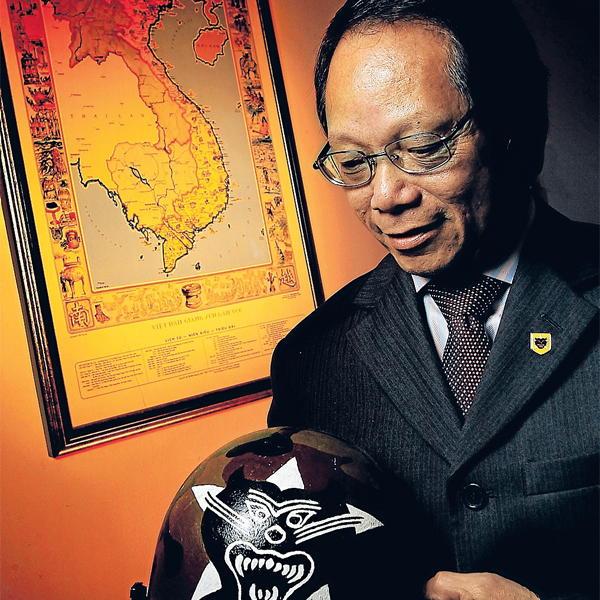

The quietly spoken, impeccably mannered Mr Nguyen, 65, will march with the Australian veterans from Footscray RSL this weekend.

‘‘I will be there. To prove that we were soldiers serving our country and to march alongside our heroes.

Asked if he would like more Australians to know about the actions of the South Vietnamese soldiers, Mr Nguyen says there was a lot of propaganda at the end of the war.

‘‘The US said Vietnamese troops did not want to fight, they were bad troops. But with us we were fighting with all our courage and we’re proud, even though we lost the war.’’

Mr Nguyen was born in the north of the country not far from the capital Hanoi.

Tensions grew following the end of the war against the then French Colonial rulers and his father, a member of the Vietnamese Nationalist Party, fled with the family of eight to the south following the partition of the country in 1954.

Mr Nguyen was just eight years old. ‘‘The French and the Viet Cong agreed that anyone who wanted to go the new south could go, so we migrated to the south.

‘‘My dad knew what the Viet Cong, the communists, would do [to opposition people] so we left.’’

After a short time in a Saigon refugee camp the family settled and Mr Nguyen studied to become a solicitor.

The clouds of war, meanwhile, had darkened and the simmering tensions between the north and south had resulted in all-out war in the 1960s with large-scale US military involvement followed soon after.

‘‘At that time our country was totally mobilised so if you were 17 or 18 years old you had to join the army unless you study, then they let you finish your studies. The government let me finish university, then I joined the army,’’ Mr Nguyen says.

Mr Nguyen was called up to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam in 1972 and was sent to an officers academy.

After graduation, he joined a battalion of the Rangers, or, Biet Dong Quan, highly skilled infantry units taught to operate deep behind enemy lines.

‘‘It’s your duty to serve. You cannot sit down and let someone invade your home. They’d kill you anyway.

‘‘Because I had a law degree I hoped I could join the military police. I couldn’t do that so I said, ‘OK, if I have to fight I wanted to fight with bravery and with professional soldiers’ so I joined the Rangers,’’ he said.

‘‘I wanted to be fighting directly with the Viet Cong.’’

Mr Nguyen was posted to the city of Pleiku in the country’s central highlands where thy were tasked with recapturing the Viet Cong stronghold of nearby Duc Co.

‘‘I was the platoon leader of a reconnaissance platoon so we went first to see how strong they were. On the way I was very worried because one wrong decision and you’re soldiers could die. I looked around and they were all very experienced and told me ‘Andy, you’re an officer, calm down’. So I calmed myself down.

‘‘At the battlefield there was not trees of shelter so the Viet Cong were able to fire at us. There was only one way and that was to attack.’’

Weeks later he was wounded but fought on after receiving a machete blow to his elbow in hand-to-hand combat at night.

‘‘He went to slash my face but I put my arm up to protect myself and he slashed my elbow. That’s where my first soldier died, in that battle.’’

His final action would come in a three-battalion-strong night-time attack on a large enemy base in late 1973. By then he had risen to rank of 2nd Lieutenant

‘‘We didn’t know who was enemy and who was friend so to find out you had to touch each other. The Viet Cong carry their ammunition bag on their chest, we carried it on our waist. If you touch a man and he had something on his chest it was a Viet Cong soldier.

‘‘When we reached the tunnel, trying to capture the artillery I was wounded. When I woke up I was in hospital. I felt it [hit me]…then that was it. ’’

A piece of shrapnel entered his chest above his right breast – he still bears a large scar – ending his war close to the end of 1974.

‘‘Not long enough,’’ he says solemnly about his own involvement.

His wounds were serious enough to qualify for discharge and he returned to civilian life as a solicitor.

Yet for all his bravery, it’s the Australian troops sent by their government to defend his country that are his heroes.

‘‘If I protect my country it’s common sense. But someone comes to protect your country, even if they were sent by their government but they still came and they are heroes. I tell them they are my heroes in my mind.’’

He would stay in Saigon after it fell and endure the communist ‘‘re-education’’ campaign in which thousands of former South Vietnamese soldiers were killed.

‘‘If you were an army officer, regardless if you’re retired or still with the force you have to offer themselves to them [communist government]. At that time I declared I was a solicitor so they let me stay and didn’t send me to what they call a ‘re-education camp’.

‘‘They don’t want to kill you because there are so many of us [former soldiers]. They way they did it was to send you there to the camp and just let you die there. If you die it’s because you cannot cope with the situation. Then they say they cannot be accused of killing you.’’

In 1981, he fled Saigon after several attempts to either leave together with his family or separately, he finally boarded a boat and left Vietnam.

In a Malaysian refugee camp he learned that the Australian government’s relationship with the new communist regime meant he would have better chance of being able to sponsor his wife and son to Australia.

Before he could get word to his wife about the possibility of sponsorship, she had boarded a boat with their son. Their son’s crying struck fear in the other refugees who demanded the child be thrown overboard.

It was only in the intervention on a fellow passenger that saved his son’s life. He is now a doctor.

‘‘Every year he marches with me. The war is over but that doesn’t mean you don’t have your memories.

‘‘We’re very proud to be Australian and Australia helped me and my family so we want to help Australia.’’

The Footscray RSL Anzac march starts at 1.45pm on Saturday from Barkly Street and heads to the sub-branch on Geelong Road for a 2pm service.

Details: 96872533 or footscrayrsl@iinet.net.au