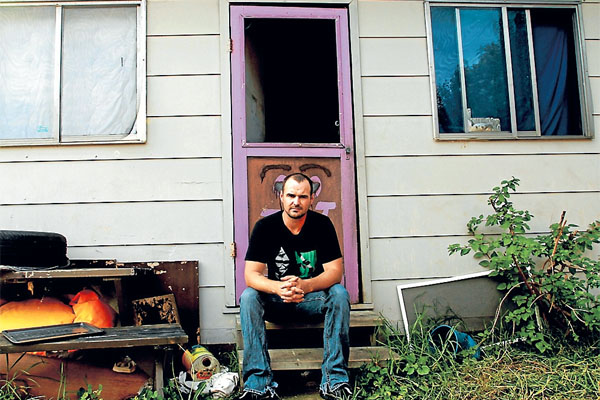

IF it wasn’t for a rooming house, Matthew Whittingham says he’d still be sleeping in his car.

He says he’s been “going through a rough time” as a result of his then-girlfriend “cleaning out” his bank account and taking off with his best friend.

He was unemployed at the time and was soon homeless, unable to pay rent. After three months of sleeping in his car, the Salvation Army housing service found him lodgings in a rooming house.

“It’s not too bad,” he says, “it’s better than sleeping in my car. If it wasn’t there I’d have nowhere to go.”

He lives in the five-room house in Sunshine West with four other people and pays rent to the landlord, who comes to collect it.

The house is “neat and tidy”, the tenants keep to themselves, and now that he’s back on his feet he’s waging a custody battle for his daughter.

Tenants Union of Victoria spokesman Toby Archer said a report by RMIT’s Professor Chris Chamberlain, which reveals an eight-fold increase in the number of rooming houses in the west between 2006 and 2011, confirmed what his group had long known.

He said the rooming house sector was flourishing under the confluence of long waits for public housing and an expensive private market.

To rein in rogue operators, the tenants union wants a central register of operators who would be struck off for poor management or criminal behaviour.

“You can have a property that complies with building and health regulations, but you can also have an operator with a 30-year track record of ripping people off and there’s nothing to stop them doing it in the future. Rooming houses are a necessary and important part of the housing system. We don’t think they should be abolished; we think they should be registered and we need to be proactive in ensuring good dwelling standard and good management standards.”